| ~ |

From Mandala to Meander

In Book One, Part One, the Garden was seen as a place of

containment and order, as a safe mandalic enclosure. In

the Wilderness the symbolism makes a right-angle turn into an

untamed landscape of shifting sands, and for what will prove to be a very long meandering

journey.

If the Garden was a watered place of comfort and consolation,

the Wilderness is where the soul experiences alienation and barrenness.

If the Garden was where the soul walked and talked with God along

bordered paths, the Wilderness is where it finds itself alone

and uncertain of the way.

As the journey had its beginning in the edenic womb of unconscious

wholeness, so in the Wilderness the soul becomes conscious

of being lost. "When a man believes himself to be utterly lost," Luther posits, then it is that "light breaks."(1)

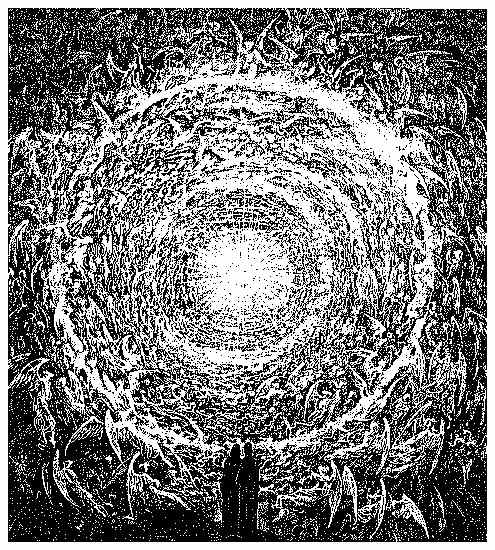

Having sensed its separation, the soul now seeks its return. Having set its sights towards the light, the soul now progresses towards those radiant beings who, having completed their own journeys, serve now as the attracting force--as the enlightened beings composing Dante's spiraling Celestial Rose. (Figure 1)

|

|

|

The Path of a Meandering River

Figure 2 |

Fretting towards Wholeness

Corresponding to Dante's imagery of Purgatory is the slow, repetitive rhythm by which the Israelites make their

way back to the Promised Land. Both Purgatory and Wilderness speak of how

consciousness is gained progressively--in stages. The Israelites, in slow, recursive twistings

and backward turnings transverse a meandering

course. Time and again, when they are nearly there, the labyrinthian

path takes them back out and away from their goal. For forty

years they are led round and round over increasingly familiar-feeling territory.

Does their meandering course begin to sound familiar? In like

manner do we not also travel time and again over the same emotional

territory? The familiar jab of an old jealousy here? The fear

of failing again there? Or the recurring nag of old anxieties,

guilts, angers? In these and numerous other ways the soul frets

its way towards wholeness. It meanders according to a

pattern so named after the winding Miandros River. (Figure

2)

|

|

| ~ |

The Labyrinth as a Pattern of Movement

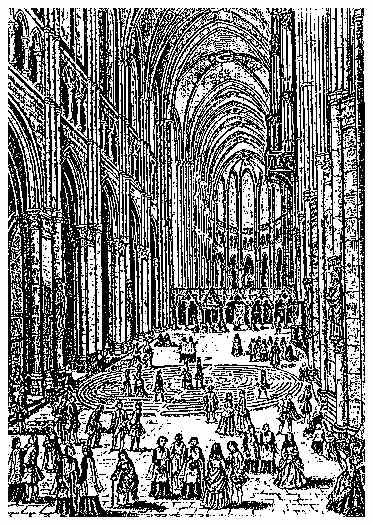

A labyrinth is a stylized meander. As a pattern of movement

it is symbolic of the soul's journey back to God by way of

the Wilderness. Dr Max Oppenheimer, a professor of foreign

languages, notes that in Arabic the word for labyrinth is matahah

which means "wilderness, desolate barrenness, wasteland."(2)

From within its pathways the overall design of a labyrinth is

obscured. Only when viewed from above is its path seen as purposefully

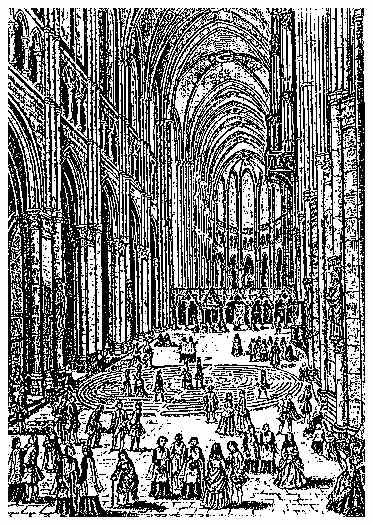

ordered and deliberately leading to the center. A prime example

is the Labyrinth in Chartres Cathedral which dates back to the

Thirteenth Century when it was popularly called Chem de Jerusalem--a

"Journey to Jerusalem" for stay-at-home pilgrims. (Figure

3).

An 18th Century Engraving of the Chartres Labyrinth

Figure 3 |

|

|

The Fret, Key, or Meander Motif

Figure 4

|

Remnants of another design, known as the "Classical," "Cretan," or "Seven-Circuited"

labyrinth, have been found all over the world. For the Hopi the design symbolized Mother

Earth; while on the coins of ancient Crete, sometimes the motif was centered by a rose, sometimes by a crescent moon, indicating devotion to the Goddess as both Mother and Virgin.

In a remarkable way, the Hopi/Cretan Labyrinth evolves out of a

familiar pattern. (Figure 4)

English geomancers, Jeff Saward and Nigel Pennick,(3) have demonstrated

how when two units of the above pattern are rotated a full 360

degrees (one axis moving, one remaining fixed), the result is

a Seven-Circuited Labyrinth. (Figure 5)

The Conversion of Meander into Labyrinth

Figure 5

Still another type of meander (Figure 6) suggests a path of movement similar to the one the Israelites

followed from their point of departure in Egypt to their place of

entrance into the Promised Land. In design, meander and maze differ from the Classical Labyrinth in which the same path that leads to the center

also leads back out again. The Wilderness is the maze--the chaos--that must be gone through on the way from one state of consciousness to another.

A Stone-etched Native American Meander(4)

Figure 6

|

|

| ~ |

Moving Towards Resolution

In 1988, inspired by the labyrinth research of Saward and Pennick, and with the help and enthusiasm of friends and neighbors, we created a Seven-Circuited Labyrinth in a meadow on our Sierra foothills ranch.

Using a knotted rope

for a compass, and after marking out the design with cornmeal, we placed stones from the

creek--one right next to the other--so as to create the alternating--clockwise/counter-clockwise--path to the center. Over the years the many who walk

it repeatedly describe their experiences as "centering,"

"quieting," "balancing," "healing."

(The Murray Creek Labyrinth)

Walking a Labyrinth is a symbolic way of moving from an outer

to an inner place--from the periphery of outer activity to a still

center of peace within. Correspondingly, the Wilderness is a

symbolic movement between two states of mind: an edenic or unconscious

state of awareness; through an unsettling transition of feeling

lost; but continuing on until a new state or level of consciousness--the

Promised Land--is attained.

Following a meandering path also can be a way of moving

towards a resolution, particularly when one's peace of mind has been upset,

perhaps by a disturbing dream, or an attack of anxiety, or an outburst of emotion.

In these circumstances movement that is circular and repetitive

has a way of bringing the source of the disturbance into

focus--into the center--there to be seen from other points of view--reviewed from all angles--thus broadening and balancing one's perception of the situation. In this

manner, we are restored to that state of mind the Bible calls Jerusalem--City

of Peace--and which the Psalmist describes as a city that is "at

unity with itself."(5)

|

|

|

~ |

Nature's Pattern of Movement

In walking a maze, a labyrinth, or some other meandering path,

the course that is followed winds first one way and then the other,

thus imitating one of nature's favorite ways of slowing things

down. Moreover, the quieting rhythm has the effect of

calming the spirit. I recall my mother telling me

that when something would be troubling my grandmother she

would get down on her hands and knees and scrub the floor--whether

it needed it or not. And that when she would get up and stand

back to admire her "clean-enough-to-eat-off-of-floor,"

whatever the trouble had been would appear to have been resolved.

Of course, that was before the age of psychotherapy. And it

is also true that much in our ancestors' lives went unresolved

and has been left to subsequent generations to work out. Nevertheless,

our lives are the better when they include movements that have

the power to restore our sense of harmony and inner peace.

Weaving, knitting, even doodling, are kinesthetic ways of experiencing

what it is to move more slowly and circularly, going for a while

in one direction and then another, one way giving way to another,

in a manner similar to a river winding its way to the sea--or

the soul back to its Source.

In Patterns in Nature, Peter Stevens explains how and why

the river winds and turns so as to slow down its movement.

At first we might suppose that the river follows the terrain,

that it twists and bends in direct response to peaks and dips

in the landscape. . . . [However, even] on a smooth and gentle

slope, we find that water does not flow straight downhill; it

wanders back and forth like a skier running a slalom.(6)

According to Stevens, the bends of a river are predictable. "The

windings turn out to be surprisingly regular, quite independent

of subtle changes in topography." The curves of rivers are

"elliptic integrals" (Figure 7) which have

the exceptional characteristic of being the smoothest of curves,

of having the least change in the direction of their curvation.(7)

How Rivers Curve Elliptically

Figure 7

Contrary to what we may have thought, the slow meandering way by

which the Israelites moved through the Wilderness just may have been the best

possible way for attaining their goal, at least when considering that

consciousness, like the river, is gained slowly and in accord with a wisdom

inherent to the nature of the soul.

|

|

| ~ |

The Dry and Thirsty Land

In the Wilderness the soul learns what it is to hunger and thirst

not for what satisfies the physical, mortal body but for what

satisfies the deeper longing of the eternal Self. It is this

dry and thirsty inner landscape about which the Psalmist wrote:

Eagerly I seek you;

my soul thirsts for you,

my flesh faints for you,

as in a barren and dry land

where there is no water.

Psalm 63:1

In the symbolism of the Wilderness, the mystic, the depth psychologist

and the alchemist share a common language and a common goal.

Their point of convergence is their concern with the soul's formation

into a vessel of Spirit. The Wilderness is both where and how

this takes place. It is therefore the "extremity" that

is God's "opportunity."

|

|

| ~ |

The Alchemist's Calcinatio

Stark and empty, the limestone Wilderness of the Bible is a place

of dry bones made white by the sun's relentless rays. For the

mystic it is the first of a three-fold progression from purgation

to illumination to union. For the alchemist it is the stage of

the opus known as the calcinatio. Edinger points

out that most alchemical images derive in part from chemical procedures.

Calcinatio relates to a drying-out process that involves

intense heat. The result is quicklime--a whitened, powdery substance.

Alchemically, this whitened "fire" acts on the nigredo--the

soul's darkness--so as to purge and purify.

When quicklime is mixed with water a catalytic reaction creates

an intense, internal heat, a heat that is inherent to the quicklime

but inert until quickened by being moistened. If the mixture

in its fluid state is poured into a mold it will "cure"

into the shape of the mold. For the medieval alchemist and mystic,

Christ was the mold into which their souls were being poured.

Most of us, when we were children, experimented with a process

in which we mixed plaster of paris with water and poured it into

a mold. What would have made our experiments "alchemical"

would have been our intent and awareness that what we were doing

outwardly had an inner correlation. Something ordinary was in

the process of being transformed into something extraordinary--something

as base as lead into something as beautiful and valuable as gold.

For the alchemist, the "chemical" procedure "rang

true" or "bore witness" to a corresponding spiritual

truth.

As Edward Edinger observes in his book on the symbolism of alchemy, when Jung discovered the writings of the alchemists, they struck in him a resounding chord:

I had very soon seen that analytical psychology coincided in a

most curious way with alchemy. The experiences of the alchemists,

were, in a sense, my experiences, and their world was my world.

This was, of course, a momentous discovery: I had stumbled upon

the historical counterpart of my psychology of the unconscious.(8)

|

|

| ~ |

Igniting the Inner Fire

For the alchemist each of the four elements was relevant to a

particular stage of the opus. For the calcinatio

it was fire, a fire inherent to this stage of the transmutation

process but inert until activated. Corresponding

to the symbolism of the calcinatio is the mystic's impassioned

desire for union with God--to be divinely enflamed.

Similarly, in order for individuation to be initiated there must

be a quickening within the psyche. Moreover, once ignited the inner fire

must be kept burning; otherwise better it had been left unlighted,

for fear of falling under the scathing indictment of the church

of Laodicea:

Would that you were cold or hot! So, because you are lukewarm,

and neither cold nor hot, I will spew you out of my mouth.(9)

In both the alchemists' calcinatio and the Israelites'

Wilderness ordeal, the soul's purgation is a process by which the hidden or unconscious

"dross" is exposed to the light of consciousness,

and in that light--that fire--is consumed. For those aspects

of a person's life that are being lived out of egocentricity

this stage of the process amounts to a "trial by fire"--to

subjection to an internal heat, but

from which ashes, as with the mythical Phoenix, the soul emerges

reborn. Figure 8

The Phoenix rising from its self-inflicted

exposure to the full force of the sun's rays (10)

Figure 8

|

|

| ~ |

The Scriptural Basis for Purgatory

The symbolism of Dante's Purgatorio, in addition to paralleling the symbolism

of the Wilderness, corresponds as well to the depth psychology

of the alchemist. Edinger, in fact, sees the "doctrine"

of purgatory as "the theological version of calcinatio

projected onto the afterlife."(11) He cites Paul as the

scriptural origin of the purgatorial imagery in which the theme

of "salvation in Christ" is presented as a trial by fire.

. . . if anyone builds on the foundation with gold, silver, precious

stones, wood, hay, stubble--each man's work will become manifest;

for the Day will disclose it, because it will be revealed with

fire, and the fire will test what sort of work each has done.

If the work which any man has built on the foundation survives,

he will receive a reward. If any man's work is burned up, he

will suffer loss, though he himself will be saved, but only as

through fire.(12)

The Wilderness is the refining furnace in which the wood, hay

and stubble are consumed. But it is also where the gold, silver,

and precious stones are revealed.

In the legend of the Phoenix, as its lifespan nears an end, it

gathers twigs and resin into a nest on which it then sits until

the intense heat of the desert sun sets both nest and bird on

fire, but out of which ashes it arises reborn.

In a Wilderness experience, at the same time the unconscious underpinnings

of a person's life are being exposed to the light of consciousness,

the soul's desire for God is intensifying,

and so consuming all lesser desires. In this way the soul experiences

what the legend of the Phoenix, as well as the alchemist's calcinatio,

symbolize.

|

|

| ~ |

Letting Go of self-Will

In the Garden, the central motif was a fountain from which four

rivers flowed out and around in a balanced rhythmic symmetry so

as to form a pattern of movement around a center. As long as

the center held the image was one of wholeness and connectedness.

But in the Wilderness the old center has let go and the new one

has yet to be established. For now the image of wholeness is lost.

Movement is disordered and diffused. The symmetry and balance

of the Garden are lost.

Jeremiah provides a pertinent illustration: One day Yahweh, wishing

to instruct Jeremiah concerning his relationship with Israel,

tells the prophet to go down to the shop of the potter and watch

him at work at his wheel. When Jeremiah arrives he observes the

hands the potter shaping and forming a vessel of clay as the wheel

turns round and round. But as Jeremiah looks on he sees the clay

begin to wobble and the vessel to teeter off balance. From side

to side it flops about until finally it collapses in on itself.

The vessel is spoiled. But the potter, all in a day's work,

simply picks up the clay and reworks it "into another vessel,

as it seemed good to the Potter to do."(13)

Jeremiah understood that Yahweh was the Potter and Israel the

clay. Relevant to our contemporary lives, God is still the Potter but

the individual soul is Israel--is the clay. And as with Israel,

the Wilderness is the phase of the spiritual journey where the

soul is formed and reformed, until, like the clay under the Potter's

hands, it learns to let go of self-will.

|

|

| ~ |

Reordering Priorities

Human nature is multi-leveled, each level with a will of its own:

the instincts willing one thing; the ego another; and the Self

still another. Each also has a hierarchy of conflicting priorities.

The Wilderness necessitates a reordering of these priorities.

What previously were considered "necessities," in the

Wilderness are reduced to "amenities." But here also,

while days are directed towards what is essential to survival,

nights afford time for soul considerations: for

measuring the hardships of the moment against the hope of eternity.

In this natural balance between day and night and body and

soul, the ego's sense of importance is all but left out. For

the ego, with all its complex needs, the Wilderness is a time

of being emptied and diminished. But it also affords the ego an opportunity

to gain a new perspective from which to re-evaluate its own

dim light against the brilliance of the starry sky, and to measure

its self-importance against the immensity of the heavens. For

the soul the Wilderness is an opportunity to gain true

humility.

|

|

| ~ |

The Nekyte

Because the Wilderness symbolizes the vast unclaimed, untamed

territory of the unconscious, the account given in Exodus is descriptive

of a prolonged encounter with the unconscious. Its overall symbolism

is suggested in its beginning crossing of the Red or Reed Sea.

Not surprisingly, the mythological roots of this crossing are

found in the Egyptian symbolism of the Nekyte, or Night

Sea Journey. Here night is the realm of the unconscious and sea

is the collective or archetypal psyche.

In crossing the sea the Israelites were embarking on a journey

that corresponds to the one the sun makes nightly in its descent

from the western sky and as it travels under the sea and through the

realm of darkness, moving eastward and unseen until it re-emerges with the

light of a new day. The symbolism is that of life/death/rebirth--the

rhythmic heartbeat of ongoing creation.

In its rising and falling, the sun corresponds to the experience

of alienation which occurs with a similar regularity as the

ego alternately and cyclically experiences inflation followed

by deflation. Its deflation feels like death, but in its rising

up it feels once more in control. This, however, sets another

cycle in motion that takes it back down again into unconsciousness.

The cycle of alienation is, according to Edinger, the way consciousness

increases incrementally until a point is reached where the ego/Self

axis of communication is sufficiently strengthened so that the

inflation/deflation extremes can be modified through an ongoing

inner dialogue between ego, instinct and Self.

Edinger has observed that Eden was paradisal because consciousness

had not yet appeared and there was therefore no conflict pressing

for resolution.(14) Here again, the Wilderness is opposite to

Eden in that it is where what is hidden and unresolved is brought

to light. With each descent and awakening of consciousness

our eternal lives are being saved from the oblivion of unconsciousness.

In Jungian terms, the path through the Wilderness is the path

of individuation, a commitment to which, Edinger notes, there

is no turning back:

the prolonged dealing with the unconscious--the chaos or prima

materia--that is required following an irrevocable [emphasis

mine] commitment to individuation . . . [is a] transition between

personal, temporal existence (ego) and eternal, archetypal life

(Self). Thus the forty years of wandering in the wilderness signify

a nekyia or night journey from the ego-bound existence

of Egypt to the transpersonal life of the Promised Land.(15)

|

|

| ~ |

Dark Night of the Soul

The biblical account of the Wilderness journey contains symbols,

images and metaphors that are relevant to those times when unconscious

contents press upwards into the foreground of our lives, inundating

and thus confounding and overpowering the conscious mind. Such

an experience is comparable to the phase of the mystic's journey

called the Dark Night of the Soul. In this Night the ego is defeated

in its efforts to remain master of the soul. Its loss of power

is a death that both alienates and purges. St John of the Cross

describes not just one dark night but one that is followed by

a still darker night:

The first purgation or night is bitter and terrible to sense,

. . . . the second bears no comparison with it, for it is horrible

and awful to the spirit.

For this Divine purgation is removing all the evil and vicious

humours which the soul has never perceived because they have been

so deeply rooted and grounded in it; it has never realized, in

fact, that it has had so much evil within itself. But now that

they are to be driven forth and annihilated, these

humours reveal themselves, and become visible to the soul because

it is so brightly illumined by this dark light of Divine contemplation

. . . .(16)

|

|

| ~ |

Alienation

In seeing the Wilderness as the classic symbol for alienation,

Edinger describes it as the "necessary prelude to awareness

of the Self." He quotes Kierkegaard:

. . . so much is said about wasted lives--but only that man's

life is wasted who lived on, so deceived by the joys of life or

by its sorrow that he never became eternally and decisively conscious

of himself as spirit . . . which gain of infinity is never attained

except through despair.(17)

Wilderness is, in fact, synonymous with alienation. It

is the long drawn-out process by which the ego is emptied of self

will. As a rule a person is driven into the Wilderness

by some inner or outer compelling circumstance: as when Adam was

"driven" from the garden;(18) or Cain "banished"

to the Wilderness as a fugitive.(19) Jacob, also, having aroused

his brother's fury, was forced to "flee" for his life.(20)

And Joseph, having provoked his brothers' jealousy, was first

"thrown into a pit" and then sold into slavery.(21)

Moses' fate was similar when, having killed the Egyptian, he

"escaped" into the Wilderness.(22) Even Abraham experienced

estrangement when he was sent by God from his kindred and his

native land in order to receive The Promise that from his descendants

a great nation would arise.(23)

|

|

| ~ |

Barrenness

What alienation was to the forefathers of Israel, barrenness

was to the women. If the Wilderness was where the soul was made

ready for the seeds of God consciousness to take root, barrenness

was the pattern for the wives of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob. Having

known barrenness they could conceive "the first fruits"

of the new potential for consciousness.

First there was Sarah who, at age ninety, laughed when told she

would conceive. Then there was Rebecca for whom Isaac "prayed

to the Lord . . . because she was barren."(24) And even

though Jacob fathered the twelve sons who became the twelve tribes,

Rachael, the only true love of his life, was also barren. Finally,

however, she did give birth first to Joseph and later to Benjamin.

And although Jacob dearly loved Benjamin, it was a love saddened

by the death of Rachael at his birth. Again of Hannah it was

said that "the Lord had closed her womb," but opened

it when she fervently prayed for a son, and Samuel was born.

In the New Testament, Elizabeth was past childbearing years when

John the Baptist was born. In each of these biblical cases barrenness

preceded the conception of a child who became a noteworthy servant

of God.

Symbolically understood, barrenness is the soul empty of self

and surrendered and receptive to God's will. It is therefore

a soul within which the seeds of spiritual awareness can come to

fruition.

|

|

| ~ |

Wounding and Healing

In alienation the thing that is lost is the old order of one's

life. It is the loss of what formerly had seemed fulfilling,

a loss of one's hard-won adaptation to life. In alienation the

ego falls from its place as king pin. Due to a combination of

circumstances, one's life is propelled into a crisis, one that

even may be life-threatening. Fears, doubts, deep anxieties surface.

Old issues and whatever other demons are waiting in subconscious

recesses appear or reappear. The outcome, even in victory, is

both wounding and healing; as when Jacob wrestled with the angel

until he "prevailed" and received from the angel a blessing,

but ever after walked with a limp."(25)

Jacob Wrestling with the Angel

Figure 9

Most Jungians, I assume, see Jacob's angel as his shadow,

and his victory two-fold: the overcoming of his fear of Esau's

revenge; and his release from guilt over having "stolen"

Esau's Blessing. Even though he "prevailed" during

that long dark night, he endured a fear so terrible that it left

its mark. He was able to endure because something in him wouldn't

let go until he "owned" rather than justified his wrong

doing, and saw his deceit for what it was. Empathy was born in

Jacob that night as he imagined himself in Esau's shoes and how

painfully hurt his brother had been by what he had done. It was

this that enabled Jacob, the very next morning, to humble himself

before Esau and, as a result, receive his brother's forgiveness.

|

|

| ~ |

The Fate of Icarus

Jung speaks of the "defeat of the ego" as when we come

to the realization that the ego--the "I" that we thought

we were--is no longer the master of our life. The "I"

has become divested of its self-importance. The result can be

devastating, as with Adam when he was driven out of Eden into

a strange land, estranged also from God whose spirit had breathed

life into him. Thus separated from his origins, his sense of

acceptance and his self-esteem were also stripped away. He no

longer knew who he was or the purpose for which he had come into

being. Adam's expulsion from the Garden, in addition to being

individually relevant, also speaks portentously of a collective

time of alienation which marks each evolutionary transition

away from unconsciousness towards a new and greater level of consciousness.

In Ego and Archetype Edinger spells out the "cycle

of alienation": how and why the breach between ego and Self

occurs and how the connection is restored. Alienation, he explains,

is the hubris brought upon through the ego's identification

with the Self. This is the sin of pride, of presumption. When

the ego identifies with the Self, presuming to be God, it becomes

inflated and brings upon itself "the fate of Icarus."

Like Icarus the ego insists on following its own course; becomes

exhilarated by its ability "to fly;" flies too close

to the sun; its wax wings melt; and Icarus falls into the sea.

The flight is its inflation; the sun its self-exaltation; the

wax wings its vulnerability; and the sea its deflationary fall

back into unconsciousness.

Through repetitions of the cycle of alienation, and particularly

as we experience the consequences, we come to recognize the ego's

self-defeating patterns and the telltale signs of its inflationary

attitudes. Here again it is Edinger who helps us identify our

inflationary tendencies by which we also fly too close to the

sun:

Power motivation of all kinds . . . . Whenever one operates out

of a power motive omnipotence is implied. . . . Intellectual

rigidity which attempts to equate its own private truth or opinion

with universal truth . . . [This] is the assumption of omniscience.

Lust and all operations of the pure pleasure principle . . .

. Any desire that considers its own fulfillment the central value

transcends the reality limits of the ego and hence is assuming

attributes of the transpersonal powers.(26)

The illusion of our own physical immortality is another

aspect of inflation. Edinger explains why a close call with death

is so often a humbling and a soul-awakening experience:

There suddenly comes a realization of how precious time is just

because it is limited. Such an experience not uncommonly gives

a whole new orientation to life, making one more productive and

more humanly related. It can initiate a new leap forward in one's

development, because an area of ego-Self identity has been dissolved,

releasing a new quantity of psychic energy for consciousness.(27)

|

|

| ~ |

Dante's Wilderness

In the Divine Comedy Dante's "wilderness" was

a "forest" which he entered through the gateway of a

mid-life crisis. His entrance was signaled by a "darkening"

or "confounding" of his conscious mind--the dark night

of his soul.

In our own journeys, the onset of a time of transition is typically

felt as a time when the meaning and purpose of life seems to have

run out. Without being able to pinpoint why, something is not

working. The direction of life feels wrong. The flow of life

feels blocked. Doubts, fears, and confusion plague the mind.

There is a sense of being entangled or trapped. But at the same

time one feels urged and compelled on, towards some unknown but

more satisfying goal in life. Thus Dante found himself at the

entrance into a "dark wood."

The wildness of that rough and savage place,

The very thought of which brings back my fear!

So bitter was it, death is little more so.(28)

Helen Luke sees, in Dante's words, the image of a man stumbling

about in darkness without any sense of direction. In other words

one who is "lost" in the psychological sense of the

word.

but the poet is surely also telling us in those few words that

it is precisely through the terrifying experience of the dark

wood that we find the way of return to innocence; that indeed

it is because of his lost state that a man is able consciously

to refind himself.(29)

Dante had awakened to the fact that the light, the meaning and

purpose of his life, had gone out. He had lost the sense that

his life was going somewhere. The forward movement had come to

a halt. He was stuck. Moreover, he seemed helpless to get his

life back on track. Something like this happens to each of us

wherever or whenever it is in life that we wake up to the realization

that we are stumbling around in the dark, and that our complacent

goals of power, success, respectability, rebellion, uplift, or

a thousand others are empty and meaningless.(30)

|

|

| ~ |

The Narrow Gate

Entering into a "dark wood" is similar to the "narrow

gate" described by Jesus as leading to life. Kunkel enumerates

what must be left behind

All security, all guarantees, . . . not only health, mammon, the

old-age pension, and life-insurance, but also reputation, social

standing, and religious merit. Moreover, the gate is so narrow

that only single individuals can pass through it. The group,

the tribe, the community, even the new brotherhood, have to be

left behind.

The gate can be found at the end of our physical career, or between

two periods of our life; or there may be many gates of different

degrees of narrowness. The narrow gate symbolizes rebirth.(31)

In light of Jungian thought, to enter through the narrow gate

is to be put in conflict with our most basic and for the most

part unconscious attachments to life. The wide gate is

the way of unconsciousness; the narrow gate the way of consciousness.

The wide gate is unchallenging: The narrow gate is wrought with

conflict, is, in fact "bought" with conflict. No wonder

so few choose the one, and so many, by not choosing, opt for the

other.

The Life That Is Lost / The Life That Is Found

Fritz Kunkel identifies "the core of Christianity" in Jesus'

statement concerning the necessity of "losing" one's

life in order to "find" it and which seems to ask that

we let go of all we hold dear in the areas of physical comfort,

temporal security, and social standing. Another way of understanding

what it is to "lose" one's life is offered by Elizabeth Boynton

Howes(32). She suggests we examine the self-protective

walls by which we "hedge in" "the vital spark of

being." We spend our whole lives, she says, building these

walls through our "defenses, evasions and excuses."

In hiding behind our walls we hide not only from others but also

from God and even from our own true selves. These self-imposed

barriers cut us off from life itself. The result is a loss of

savor for life. In our attempt to "save" ourselves

from the emotional hurts and pain of life we lose the opportunity

life affords us for enlarging our souls in preparation for eternal

life.

|

|

| ~ |

The Wilderness of Sin

For the Israelites the Sinai Wilderness was their place of despair,

a despair repeatedly attributed to sin. In fact, throughout

the Bible there is so much talk of sin that it is impossible to

seriously study the scriptures without coming to terms with this

word. Edinger points out that St John of the Cross' "dark

night of the soul," Kierkegaard's "despair," and

Jung's "defeat of the ego" all refer to the same experience,

to an awareness of lostness, of separation, of sin. Sin

in this sense is not an act but a state. And if so, it is also

the way we are found and therefore "saved." In Luther's

words:

God works by contraries so that a man feels himself to be lost

in the very moment when he is on the point of being saved. When

God is about to justify a man, he damns him. Whom he would make

alive he must first kill. God's favor is so communicated in the

form of wrath that it seems furthest when it is at hand. Man

must first cry out that there is no health in him. He must be

consumed with horror. This is the pain of purgatory . . . In

this disturbance salvation begins. When a man believes himself

to be utterly lost, light breaks.(33)

|

|

| ~ |

The Hero's Journey

In as much as the path through the Wilderness is the path of individuation,

it is the archetypal hero's journey of becoming. It is the stage

upon which egocentricity is transformed into ego strength, which

in turn is the distinctive mark of the hero or heroine whose influence

extends beyond his or her own personality. Erich Neumann notes that

the hero is one "who is destined to bring [the] new order

into being and destroy the old."(34)

[He,] the hero, like the ego, stands between two worlds: the inner

world that threatens to overwhelm him, and the outer world that

wants to liquidate him for breaking the old laws. Only the hero

can stand his ground against these collective forces, because

he is the exemplar of individuality and possesses the light of

consciousness.(35)

John Sanford, referring to Moses' birth as following the pattern of

a hero, adds "but this did not guarantee he would become

a hero."

Before the seed of a potential hero in him could develop, the

young Moses had to undergo a process of psychological development

and transformation. As with Jacob and Joseph before him, his

egocentricity had to be destroyed, so that his life could be molded

by the Greater Will within him."(36)

As clay upon the Potter's wheel each of our lives is being raised up,

sometimes into a fit vessel, but other times collapsing in on

itself. Thus we are shaped and reshaped, formed and reformed,

"as it seems good to the Potter to do." all the

while learning how to let go, how to yield self-will, what

it is to will one thing--to will the will of the Higher Will--and

so submit to the process by which the soul is formed into

a vessel of Spirit.

|

|

| ~ |

Illustration Credits

1. Gustave Dore, from Illustrations for Dante's Divine Comedy,

Dover,

2, 4, 7, the author

3. 13th Century engraving, reproduced in Labyrinths, their

Geomancy and Symbolism, by Nigel Pennick, Runestaff--Old English,

1986

5. Nigel Pennick after Jeff Saward, Labyrinths

6. After illustration in Mazes & Labyrinths, by W H

Matthews, Dover, NY 1922, Pictograph from Mesa Verde

8.

9. Pen & ink drawing by Marianne Elliott

Endnotes

1. Roland Bainton, Here I Stand, Abingdon-Cokesbury NY, 1950, pp 82

2. Max Oppenheimer, "On Labyrinths and Mazes--Meandering & Musings," in Labyrinth Letter, Vol 1, No.2, July 1995, 10550, E San Salvador, Scottsdale AZ 85258-5744

3. Nigel Pennick, Labyrinths: their Geomancy and Symbolism, Runestaff, England, 1986, p 5

4. W H Matthews, Mazes and Labyrinths, Dover, NY, Original, London, 1922

5. Psalm 122:3

6. Peter S Stevens, Patterns of Nature, Little/Brown, Boston, 1974 pp 92-3

7. Ibid

8. Edward F Edinger, Anatomy of the Psyche, Open Court, La Salle IL, 1985, p1

9. Revelations 3: 15-16

10. J E Cirlot, A Dictionary of Symbols, Philosophical Library, NY, 1962 p 253

11. Op cit, Edinger, p26

12. 1 Corinthians 3:11-15

13, Jeremiah 18:4

14. Edward F Edinger. Ego and Archetype, Penguin Books, Baltimore, 1973, p 17

15. Edward F Edinger, The Bible and the Psyche, Inner City Books, 1986, Toronto, pp 51-2

16. St John of the Cross quoted in The Soul Afire, p 256-259H A Renhold, Editor, Meridian Books NY 1960

17. Op cit Edinger, Ego and Archetype, p 48-50 and Fear and Trembling, the Sickness Unto Death, by S Kierkegaard, Garden City, NY, Doubleday Anchor Books, 1954, p 159.

18. Genesis 3:24

19. Genesis 4:12

20. Genesis 28:43

21. Genesis 37:28

22. Exodus 3:15

23. Genesis 12:1-2

24. Genesis 25:21

25. Genesis 32:31

26. Op cit, Edinger, Ego & Archetype, p 15

27. Ibid

28. Dante, Divine Comedy, I i, Lawrence Grant White translation, NY Pantheon

29. Helen Luke, Dark Wood to White Rose, Dove, Pecos NM, 1975, p 9

30. Ibid

31. Fritz Kunkel, Creation Continues, Word Books, Waco TX 1973, p 109

32. Elizabeth Boynton Howes, Jesus' Answer to God, Guild for Psychological Studies, San Francisco, 1984, p128-130

33. Roland Bainton, Here I Stand, Abingdon-Cokesbury NY 1950, pp 82f

34. Erich Neumann, The Origins and History of Consciousness, Bollingen, Princeton 1970, p175

35. Ibid, p380

36. John A Sanford, The Man Who Wrestled with God, Paulist Press, NY, Revised Edition, 1987, p83

|

|

| ~ |

|

|