CHAPTER THREE

THE INCARNATION

I

THE NATIVITY

We are no more than the manger in which the Lord is born. C G Jung 1

The Bethlehem Event

As the Annunciation is a descent from the realm of archangels to Mary’s supraconscious state of receptivity, so the Incarnation is a further step down into the world of everyday consciousness where hope and fear, light and dark co-mingle. In the biblical accounts of the Nativity, the historic and the mythic--the real and the symbolic—also intermingle. Yet considering the cosmic proportion of the event unfolding at Bethlehem, how could it be otherwise? How could the heavens not rejoice, or the earth and all of creation not be glad over the good news traveling the light waves of spirit: A child is born. His name (nature) shall be Wonderful, Counselor, Prince of Peace?2

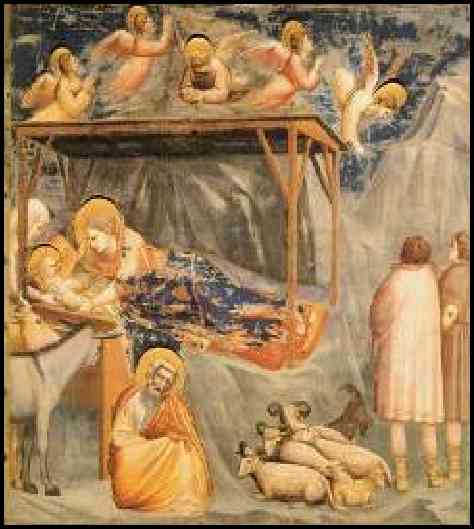

Heralding the event, a brilliant star lights the way to the

stable where the Holy Child is cradled in a manger. Converging upon the

scene are the angels and the shepherds, come to join the beasts of burden

already there to welcome the one born to bear human’s burden of iniquity. Giotto’s

thirteenth century Nativity, painted on the walls of the basilica at

Assisi, tells it all. (Plate 1)

Plate 1

The Nativity, by Giotto

As evidence that this Child’s destiny transcends that of an other infants,

“wise men” from the East follow the star that leads them to the Child. Jung

explains that

The Magi from the East were star-gazers who, beholding an extraordinary constellation, inferred an equally extraordinary birth.3

The long-anticipated celestial event is believed to have been a third consecutive conjunction of Saturn and Jupiter in the zodiacal sign of Pisces, and to have pointed to the birth of Israel’s new king.4 Jung’s comments continue:

These astrological ideas are quite understandable when one considers that Saturn is the star of Israel, and that Jupiter means the “king” (of justice.)5

Rabbi Joel

Dobin, in The Astrological Secrets of the Ancient Hebrew Sages, has

clarified that the Jupiter-Saturn conjunctions occurring every twenty years

were looked upon as favorable times for reassessing God’s will. And when

they occurred repeatedly in the same sign, they were said to herald “a major

change in the manifestation of God’s will.”6

The Changeover of Archetypal Dominants

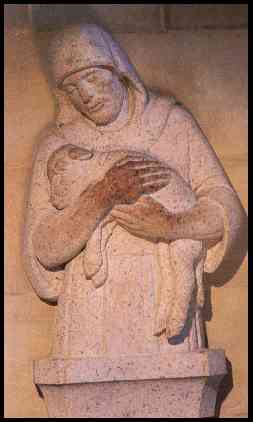

It was also a time of changing archetypal dominants. As the astrological Age of Aries, with the ram as its symbol, was ending, the Age of Pisces, represented by the two fishes, was commencing. Aries had been a pastoral age; and accordingly the first to visit the newborn king were shepherds. Moreover, the theme of “the Good Shepherd” would be woven throughout the Gospels and inspire both early and late Christian art. An example is the carved reredos in Plate 2 from the Chapel of the Good Shepherd in the Washington National Cathedral.

Plate 2

The Good Shepherd

In accordance with the incoming Piscean symbolism, the Christ

would call his followers from among fishermen and instruct them in how to

become “fishers of men.” He would multiply the fishes and loaves to feed

the multitude; pay taxes with a coin found in the mouth of a fish; and even

direct his disciples as to where to cast their nets for “the miraculous

catch.” These acted-out parables would spawn a whole shoal of fish

symbolism as well as be reflected in the religious art of the age, as in

Duccio’s painting of the calling of Peter and Andrew which is part of the

National Gallery of Art’s treasury. (Plate 3)

Insert Plate 3

The Calling of the Fishermen, by Duccio

Noting the wealth of astrological symbolism around the birth and throughout the ministry of Jesus, Jung expressed the opinion that to anyone acquainted with the symbolism of astrology it should be clear that Christ was born as “the first fish of the Pisces era, and also doomed to die as the last ram of the declining Aries era.”7

Before the Age of Aries human sacrifice was not uncommon. When Abraham thought he heard God tell him to sacrifice his only son, in obedience he set out to do so. At the last minute, however, an angel stopped him. Turning around, Abraham saw a ram caught in a nearby thicket. Thus a ram took the place of the son and became the acceptable burnt offering of the Judaic age. Two thousand years later, another “only son” would be called “the lamb of God.” To him would be entrusted the task of breaking human bondage to belief that God required any sacrifice other than a humble spirit and an open and contrite heart into which the Spirit of God could enter.

In the Age of Aries--a fire sign--the rite of sacrifice was the burnt

offering of the holocaust. In the following Age of Pisces--a water

sign--baptismal waters would be the rite of passage into new life. And now

with entry into Aquarius--an air sign--a changeover of archetypes is again

happening, with symbolic emphasis now relevant to air—to the upper realms of

space, of mind, and of spirit—and the supramental fields of consciousness

where the mystics of all ages have gone before, and where the initiatory

rite of passage well may be the same as Mary’s: “Let it be unto me according

to God’s will”—the sacrifice of self-will to God’s higher will for one’s

life.

As the outline of a fish was the earliest sign by which

Christians identified themselves, so already the dove has become the symbol

of choice for spiritual renewal. Its symbolic roots, however, reach back to

the dove of Genesis who returned to Noah bearing the olive branch of peace;

who appeared also at the Annunciation; who was perched in the rafters at the

Nativity; who descended upon Jesus at his baptism; and again as the

dove-winged tongues of fire at Pentecost to baptize the hundred-and-twenty

in the upper room with the fire of Spirit.

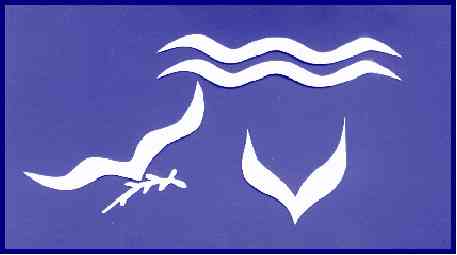

In creative design--including pictographic, glyphic,

hieroglyphic, and folk art--the wavy line expresses fluidic movement. From

early peoples on, the wind—pneuma, breath—has been a sign of the presence

and power of Spirit. Spiritual energy, electrical current, light waves,

vibrational frequencies, are all represented by wavy lines, as is the Age of

Aquarius by its glyph. Birds gliding on currents of air are similarly

indicated by a wavy line, while birds in general belong to the symbolism of

spirit. In religious art as in the scriptures, a pure white dove indicates

the operation of the Holy Spirit. At Jesus’ baptism, “the heavens were

opened” and the Spirit descended “as” a dove:

. . . and [John] saw the Spirit of God descending like a dove, and alighting on [Jesus].8

Then again at Pentecost, when the Holy Spirit came it was

like a rush of wind,” and “there appeared tongues as of fire.”9

In both instances the language used is qualifying a manifestation of Spirit. In both cases the manifestation is focalized and intense enough to materialize and appear, at least to the visionary eye, in a discernible shape: out-of-doors as a dove; in the darkened “upper room” as tongues of flame. In any event, Figure 1 illustrates the close resemblance in creative design of the essential outlines of a wave of spiritual energy, a dove in flight, and tongues of fire.

Figure 1

The Essential Outlines of Light Waves, a Dove in Flight & Tongues of Fire.

The Virgin Mother

As everyone knows, the chosen vessel for the divine/human Incarnation was a virgin named Mary. Less known is the role of Virgo in the Piscine heavens. And even though orthodox Christianity is uncomfortable with astrological symbolism, its presence in the Bible is difficult to ignore, as is the influence of the-goddess-who-never-went-away but simple withdrew into the hearts and souls of the common people. Her new name would be Mary.

Esther Harding, from a psychological perspective explains why it was appropriate that the Holy Child be born of a virgin.

Psychological virginity refers to an attitude which is pure in the sense that it is uncontaminated by personal desirousness. . . . The virgin ego is one that is sufficiently conscious to relate to transpersonal energies without identifying with them. . . . [and quoting Philo] . . . “when God begins to associate with the soul, he brings to pass that she who was formerly woman becomes virgin again.”10

Jungian analyst Luella Sibbald refers to the astrological as well as psychological relevance to the virgin birth of the Christ. She notes the Zodiac sign opposite Pisces is Virgo. This places the two constellations in a relationship that is both complementary and in opposition--mother and son, the masculine and the feminine, the son of God and the mother goddess, sun and moon, the conscious and the unconscious. Thus the heavens affirm the balancing, supportive role of Mary and the feminine principle in bringing the new humanity to birth.

In spite the strong opposition between the masculine and feminine poles of human nature that reaches back to the origins of the Hebrews, and despite the still-powerful Christian patriarchy, sometime around the beginning of the second millennium Mary’s role in human redemption began to gain recognition. Out of this there arose “the cult of Mary.” Her feminine influence, however, was more deeply felt than “popularity” and “cult” imply. In truth, devotion to “Our Lady” was a transfer of affection from the ancient goddess to a form more acceptable to the Church, a devotion that would penetrate to the very heart of the culture and creativity of the middle ages.

Sibbald has related that among those influenced by Mary’s feminine virtues were the master builders of the grandest of Europe’s gothic cathedrals, seven of which--all dedicated to “Our Lady”--were geographically placed so as to correspond to the stars making up the constellation of Virgo. The Chartres Cathedral, as the most famous of these, was situated in the most important position, while the other six, also honoring “Notre Dame,” were positioned to correspond to other prominent stars in the constellation. Thus the master architects, in an age unsurpassed for its architecture, conformed their art to the premise “as in heaven, so on earth.” Similarly, the individuation process leads to a union between the masculine and feminine poles of being. And, as the Christ Child was born of a virgin:

The divine child in each one of us can only be born from the virginal, unknown inner place, removed from the activity of the adapted, collectively oriented side.11

Continuing Incarnation

“Continuing

incarnation” is the phrase Jung used in connection with the awakening of

individual awareness to the transcendent nature of the Self. In Nativity

symbolism, the human heart is the manger in which the inner Christ Child is

cradled, and where, in the lowliness of this hidden place, it is protected.

As the inner Child “grows in wisdom and stature” the psyche in its totality

serves as its Holy Family in protecting and guiding the Self to maturity.

Plate 4 is an early nineteenth century folk art painting on glass from

Poland. It is a reminder of the role these images have played in the

spiritual life of ordinary people.

Plate 4

The Holy Family, by an Unknown Folk Artist

The songs of a people as well as their art shape their spiritual lives. At Christmas the familiar carol bids the birth of the inner Christ:

O holy Child of Bethlehem, descend to us, we pray;

Cast out our sin, and enter in, be born in us today!12

Now as with Mary, the divine birth depends upon a consent of will, and a heart in which room for the Child has been made. As with Mary, her “let it be” is how the soul also is impregnated. “Christ in you the hope of glory”13 is how Paul presents the theme of continuing incarnation. For Teilhard as well, incarnation is an ongoing Christing process; while Jung’s hope is that the time is now right--the kairos--for the “Christification” of many.

THE BETHLEHEM STAR

Figure 2

The Star-Cross of the Transcendent Self

The Star of Bethlehem, as the brightest light in the night sky, signals the sowing of the heavens with the star-seeds of the new humanity. As an archetypal symbol, the star speaks of the origin, destiny, and eternality of the soul. As the eight-pointed star-cross of the transcendent Self (Figure 2) it speaks of the individuating or Christing process.

Of all the symbolism surrounding the Incarnation, the star is the most universally recognized. Ignatius captures this in the following lines:

A star shone forth in heaven above all that were before it, and its light was inexpressible, while its novelty struck men with astonishment. And all the rest of the stars, with the sun and moon, formed a chorus to this star.14

The Psalmist as well sang of the long-awaited event:

Let the heavens be glad,

and let the earth rejoice;

. . . before the Lord,

for he comes . . .

15

Symbolically, the heavens are the psyche and earth the soma. The one star that outshines all others is the Self whose light illuminates the entire inner, microcosmic universe of the soul. About this star Edinger writes:

One star that outshines the others represents “the One Scintilla or monad” among the multiple luminosities of the unconscious and “is to be regarded as a symbol of the self.”16

In the East much is made of the symbolism of the star. There the belief is that each soul has its own star from which it originates and to which it returns. In the tradition from which this comes, persons are seen more complexly than in the West. Heinrich Zimmer explains:

We are not simple, and the duality of “body and soul” does not express our being. The ancient conception of man was highly complex, as is shown in the following lines telling what becomes of him after death:

Earth covers the bones,

the shade flies round the mound,

the soul descends to the underworld,

the spirit rises to the stars.17

An Act of Divine Imagination

Going back to the origins of Judaism, Abraham is told to look to the stars: his descendents will be that innumerable. Taken literally the promise speaks of a quantity of sons and daughters with a common ancestry. But if by progeny the reference is to the capacity to enter into conscious relationship with God, then the promise can be understood as speaking qualitatively about a higher, transcendent capacity for union with God, and a larger Reality where the eternal spiritual Self is forever at home in God.

In being

told to look to the stars, Abraham is asked to engage his creative

imagination. To look up through mortal eyes to the myriad stars against the

backdrop of the night sky is to feel insignificant by comparison. But

through the higher functions of intuition and imagination, it is possible to

observe the one star that is ours, and to see it reaching out to us. As it

grows brighter and brighter, we imagine ourselves and our star moving

towards one another--closer and closer, nearer and nearer--until we touch,

merge, and become one. Thus in imagination it is possible to ascend to the

stars, and to that “One Scintilla” that heralds the birth of the inner

Self--the true and eternal mode of being.

Myth and History

In the Incarnation the realms of the divine and the human merge. Eternity unfolds in historic time. Emmanuel! God is on earth!

In the Christ event myth and history are woven together; unless, that is, a myth is equated with a story that isn’t true. Then the mythic material in the Bible becomes troublesome. Confusing facts with truth, some insist the Bible contains the literal words of God. Others overreact to this, until between the literalists and the rationalists the beauty and truth of the Bible suffers mutilation, eclipsing its deeper meaning. But what if the Nativity is truth of an altogether higher order? What if, as Frederick Buechner holds,

A myth is a story that is always true.18

II

THE HIDDEN YEARS

The Holy Family

The Gospel accounts surrounding the birth and early years of Jesus are in all likelihood just such a mixture of historic and mythic truth. But as Jung points out, sometimes the two--the mythic and the historic--converge. Were this not so, this one life that transcended its own historic time and geographic place would not have had the transforming impact it has on millions of lives. Nevertheless, the Gospels record only three incidents involving Jesus’ early life as the son of Mary and Joseph. In the New Testament these serve as a transition from the more mythic elements of his birth to the more historically-presented accounts of his public ministry. Since each of these events relate to stages of the individuation process they are worth examining.

In Luke,

Joseph and Mary take the infant Jesus to the temple forty days after his

birth. Again it is Luke who places the boy Jesus at twelve and once more in

the temple in Jerusalem. Matthew omits these but records the escape into

Egypt. Although most of the details of these oft-told stories are

apocryphal, like the stories surrounding his birth they have been fleshed

out and made memorable as the subject of some of the greatest art of the

Christian era. Long before the common people had Bibles and could read,

scenes from the life of Christ adorned basilica and cathedral walls. As a

result these archetypal representations came to be embedded in the inner

gallery of collective images that is part of Western culture’s sacred

heritage. In showing Mary and Joseph honoring and protecting the sanctity

of the Christ Child, these familiar scenes speak also of how, in the

individual Christing process, the inner divine image needs to be

affirmed and nurtured.

The Presentation

On the first

occasion, Mary and Joseph take the infant to the temple in Jerusalem.

Mary’s forty-day “purification” is over and they go there for the purpose of

dedicating their newborn son to God. The prescribed offering for the rite

is two turtledoves. (Plate 5)

Plate 5

The Presentation, by Giotto

The present day custom of baptizing or “christening” infants is rooted in this ancient observance of the law of Moses. A “devout” man named Simeon is witness to the ceremony. After Simeon confirms the divine destiny of the Child as “a light for revelation to the Gentiles,” he turns to Mary and forewarns, “a sword shall pierce through thine own soul.”19 Also present is a prophetess named Anna “of a great age,” who for many long years has lived at the temple “worshiping with fasting and prayer night and day.”20 Recognizing the Child as the one for whom Israel has been waiting, she too gives thanks,

The Presentation is also an allegory for the attitude the ego needs to assume in relationship to the newly emerging Self. Kahlil Gibran captures the essence of the moment when possessiveness towards a child is relinquished.

Your children are not your children.

They are the sons and daughters of Life’s longing for itself.

They come through you but not from you,

And though they are with you yet they belong not to you.21

Similarly, the inner Christ Child, in its early stages, needs protection

from the ego’s possessive attachments. This is what Harding intends by the

“virgin ego” as being “sufficiently conscious to relate to transpersonal

energies without identifying with them.” Thus in Revelations, as soon as

“the woman clothed in the sun” (i.e., consciousness) gives birth to

the Child, at this moment the Dragon (i.e., unconscious “desirousness”)

appears. The Child, however, is spirited away “to the throne of God,” and

the woman (as the Christ-bearing soul) flees to the Wilderness, to a place

prepared for her by God.22

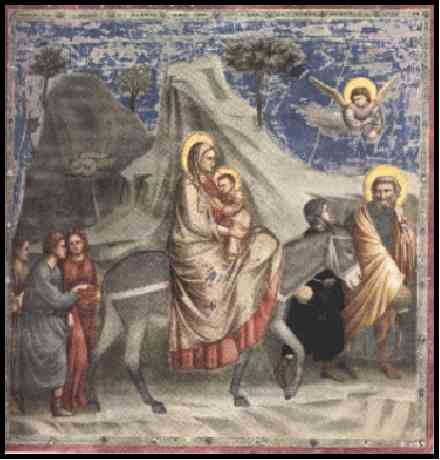

The Flight to Egypt

If the Holy Child is to survive its earliest and most vulnerable stages, it must do so under the wing of divine protection. Therefore an angel appears to Joseph in a dream, instructing him to take mother and Child “down into Egypt” out of harm’s way. Not only must Joseph, as protector of Mary and Jesus, be open to guidance but he must be willing to alter the course of his own life for the sake of the Child. Similarly, the individuating Self is worthy our unreserved commitment to its well-being, and our willingness to go wherever the process leads. This is a persistent biblical theme wherever the evolution of consciousness is at issue: Adam and Eve are forced from Eden; Jacob flees his brother’s anger; Joseph is exiled in Egypt; and Moses escapes to the wilderness.

By including the “Flight to Egypt,” the author of Matthew brings an Old Testament pattern forward and, at the same time, fulfills Hosea’s prophecy: “Out of Egypt have I called my son.”23 (Plate 6)

Plate 6

Flight to Egypt, by Giotto

The Journey to

Jerusalem

In the third

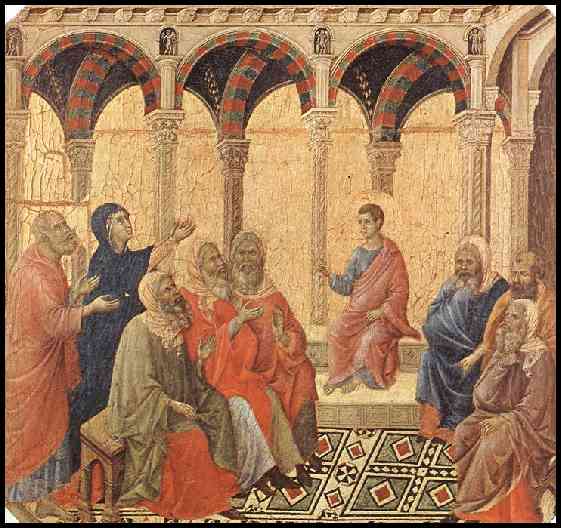

scripture vignette of the life of the Holy Family, we are told that the

Child has grown. He has “waxed strong, filled with wisdom: and the grace of

God.”24

He now is twelve, and “according to custom” has gone with Mary and Joseph to

Jerusalem for the feast of Passover. When it comes time for the journey

home Mary and Joseph assume he is with others in the traveling party. They

don’t realize he is missing until he fails to show up for supper that

evening. Immediately they turn back to Jerusalem and, after searching for

three days, find him “sitting among the teachers, listening to them and

asking them questions.”25

(Plate 7)

Plate 7

Jesus in the Temple at Twelve, by Duccio

When a child

is missing anxiety intensifies with each moment and each failed effort to

find the child, especially if the parent has grown accustomed to the child

doing as expected. Mary’s lament is typical: “Son, why have you treated us

so?” and the boy Jesus’ response is also characteristic: “I thought you’d

know where I’d be.

Is there a

conscientious parent who hasn’t known apprehension and anxiety over a

child’s safety and well-being? Or, as the child has matured, not had to

entrust him or her to Life itself, and to the wisdom inherent to the child?

It is often at this gateway to adolescence, as portrayed by the boy Jesus in

the temple, that the passion of a child’s interests point in the direction

his or her life will take. Seized by the intensity of the moment, all else

is overshadowed. Time ceases to exist, as does the possibility that parents

just might be worried, or that it isn’t obvious to them where their child

can be found.

The transpersonal Self is by nature disproportionate and non-temporal. I recall the day our youngest son didn’t come home from school as expected. Since we lived in the country we thought either he would get a ride or call for one. Only when he didn’t show up for supper did we begin to worry in earnest. Finally, at nine o’clock in the evening we began calling. Fortunately we found a friend who had left him several hours before at the pizza place in town. At that time, the friend reported, he had been playing the same electronic game for three hours straight. We, of course, called immediately; “Yes” he was still there, and still playing the same game on the same quarter.

Did the relief of my maternal anxiety express itself in accusation? Indeed! and in words close to Mary’s. “But I couldn’t leave,” he protested. “No, I couldn’t phone. I was breaking a record.” And was our child’s fascination with things electronic, coupled with a capacity for prolonged concentration, a clue to where Life would be leading him? Absolutely!

The finding of Jesus in the Temple can be turned into a personal query:

How can the Self’s call to serve Life be discerned in those times when I have been so absorbed in the moment as to be oblivious to time? and to whatever other obligations I was neglecting?

What are

the fears that have held me back from following where Self would lead? What

price has been exacted for failing to do so? And when I have followed, what

have the rewards been?

III

PRELUDE TO MINISTRY

The Missing Years

From the time Jesus is twelve until he presents himself to John for baptism, the Gospels are silent. Luke provides the date as “the fifteenth year of Tiberius Caesar’s reign.” A footnote in The Jerusalem Bible calculates this as between 28 and 29 A D. Taking into account an arithmetical error concerning the beginning of “the Christian era,” Jesus would have been between thirty-three and thirty-six years old. His “missing years” are therefore those during which most persons round out their personal lives, start families of their own, and become established in the roles they are assuming as contributing members of a community.

One place in the Gospels the question is asked: “Is not this the carpenter,

the son of Mary . . . .”26

And in another place: “Is not this the carpenter’s son?”27

No other reference to the “missing years” is made. Some suggest he might

have returned to the Egypt of his early childhood to study the ancient

mysteries. Others suggest he spent some of those years in India. Or he

simply could have blended unobtrusively into the life of Nazareth, carrying

on the carpentry work of Joseph after his death, and taking his place as the

head of Mary’s household.

Sonship and

Selfhood

Jesus’ emergence from obscurity began with his baptism. This event included some of the same symbolic elements present in the Annunciation. In Matthew, as he came up out of the waters “the heavens were opened . . . and he saw the spirit of God descending like a dove . . . and a Voice from heaven [saying], “This is my beloved son, in whom I am well pleased.”28(Plate 8)

Plate 8

Baptism of Christ,

A Contemporary

Stained-glass Window

Another Wilderness

Immediately after the Annunciation Mary had headed straight for the isolation of her cousin Elizabeth’s country home, so Jesus after his baptism “was led by the spirit into the wilderness” where for a period of forty days he was “tempted.”

A time spent in the wilderness is another familiar Old Testament theme. With forty years as the duration of the Israelites’ stay, Jesus’ forty days is an abbreviated parallel, but one that confirms the Old Testament pattern of this as a time of “temptation” or “testing.” On the spiritual journey, the wilderness is where the soul learns what it is to hunger and thirst not for what satisfies the physical, mortal body but for what satisfies the deeper longing of the eternal Self. About this dry and thirsty inner landscape the Psalmist writes:

Eagerly I seek you;

my soul thirsts for you,

my flesh faints for you,

as in a barren and dry land

where there is no water.29

The wilderness is where the soul undergoes its formation into a vessel of Spirit. In the individuation process, it is how the unconscious underpinnings of a person’s life are exposed to the light of consciousness, and where the soul’s desire for wholeness so intensifies as to turn all lesser desires to ashes, but from which experience the Self, as the Phoenix, emerges reborn.

Because the wilderness symbolizes the vast unclaimed territory of the collective unconscious, it well could take forty years to transverse. And even that might not be time enough. Whether forty years or forty days, the wilderness is a stage of transformation that takes as long as it takes. Edinger notes,

[It is] the prolonged dealing with the unconscious--the chaos or prima materia--that is required following an irrevocable commitment to individuation . . . .

[It is a] transition between personal, temporal existence [that of the ego] and eternal, archetypal life [that of the Self].30

Jesus’ forty

days in the wilderness are instructive of what can be expected when a

person’s life is intercepted by God and the course of that life altered. In

its most gentle expression, the wilderness is a time and place for sorting

out the often conflicting inner voices clamoring to be heard and by which

persons feel pulled in different directions. In essence, the purpose of the

wilderness is to determine and prepare the soul to trust and follow where

the will of God will lead.

Who is the Tempter?

Jesus’ wilderness temptations were on three levels: the first concerning “bread” was the temptation to put physical or materialistic needs ahead of spiritual ones; the second Edinger described as “the temptation to transcend human limits for the sake of spectacular effects;” and the third was to seek worldly power and glory. For this last temptation Jesus was led up “a very high mountain,” suggesting that if unrestrained the ego’s desire would be for nothing less than to usurp the place God.31

Jesus

identifies his tempter as the “devil,” which Tolstoy, in his The Gospels

in Brief, translates as “the voice of the flesh.” Fritz Kunkel,

somewhat similarly, equates the devil with a person’s own voice of

egocentricity. If the ultimate temptation is to be sidetracked from

fulfilling one’s higher destiny, then the temptation to live solely for

material gains and comforts does just that, as do the ego’s temptations to

live according to its desire for power and glory. Some are tempted more by

one, some more by another. The only real failure of a wilderness testing is

to see the source of temptation as having an outer rather than inner origin,

and so miss the opportunity to consciously identify and have it out with the

inner voices of one’s fears and other self-defeating patterns. Not to do so

is to evade one’s allotted share of responsibility for collective evil, and

something to which each is called not simply to endure but to overcome and

transform.

IV

THE POWER TO BECOME

. . . to all who received him,

who believed in his name,

he gave power to become

children of God. John 1:12

The Depth Psychology of the Gospels

As Jesus actualizes wholeness in his own being, so he sees everyone else as potentially whole, even one so hopeless as the man from Gerasenes whose demons are “Legion.”32 The story is reminiscent of Jesus’ words to Suares quoted earlier: “It wasn’t you that found me,” rather, “It is you in me that I found, in what it is your nature to become.”

As a healer of souls, Jesus’ methods were similar to those of depth psychology. Kunkel, a psychiatrist and a dedicated follower of Jesus, regarded the New Testament as “the great text-book of depth-psychology.”33 Bypassing the obvious, Jesus had an uncanny way of going right to the heart of each person’s real inner need. With both wisdom and compassion, he knew in an instant where persons were blocked; where their perspectives on life were too narrow; where their perceptions were limiting their potential for wholeness; or where their inner attitudes were undermining their outer lives.

As portrayed in the Gospels, he saw each one he met as unique. And he met each on the ground of her or his own being, He freed those who came to him from all manner of emotional and mental disturbances, but without the use of any special “technique,” or pat formulas. Rather, when he looked into persons’ souls complex physical, psychological and spiritual problems came unraveled before his unconditional acceptance and total lack of judgment towards them. With a word, with a look, with a gesture, he was able to disarm their defenses and take authority over their demons, or in Jungian parlance, the very real autonomous complexes of their inner worlds.

His

objective always was to reconnect those he encountered to the springs of

living waters from which the creativity, the meaning, and the purpose of

their lives could once again begin to flow and move them back into the

stream of life. In this way he went about “fulfilling the scriptures” and

proclaiming “the acceptable year of the Lord”—the year of Jubilee—which

brought with it good news to the poor; release to the captives; sight to the

blind; and liberty to the oppressed.34

His was a declaration, a proclamation of the new higher law of God--the law

of compassion and mercy. To those who received him he gave power to become

the children of Abba—the One who became two so that the two could return to

the One What did it matter, he asked, whether he said “your sins are

forgiven” or “take up your bed and walk”? The realm, the reign, the domain

he came to bring in was beyond form. It was without formulations. Neither

here or there, it broke forth spontaneously. Neither this nor that it was

whatever of value had been lost and now was found--the lost sheep, the lost

coin, the hope that had been lost, or the life that until now had been

unlived.

The Real and the

"Not Real"

In his role of repairing the breech between the human and the

divine, he also dealt with cases not so simple as the casting out of

demons. More difficult were the attitudes of mind that blind a person’s

eyes to the reality of the spiritual world.

As a physical being I know that I exist because of what I see, touch, hear,

smell and taste. My senses tell me this is the “real” world. And they are

so convincing that they lead me to believe that all else is “not real.”

Their judgment is against there even being such a thing as a spiritual

world. This domination of sense perception erects a prison-without-walls

that limits the soul’s access to the greater spiritual realm. Yet it is not

only the senses that create the confusion as to what is the “real” and what

the “not real.” It is also the intellect and its tendency to confuse “mind”

with “spirit.”

The Man who Comes

to Jesus by Night

Enter Nicodemus--a man seeking a way out of his similar confusion. He comes to Jesus by night, perhaps at night because his self-identity is too much with his intellect, while the restlessness that is leading him to Jesus is coming from his spirit. The intellect is rational, analytical and controlling, while the spirit is like a child, spontaneous, exuberant, expressive, and a terrible embarrassment to the dignity of the intellect. Only if Nicodemus can meet Jesus without being seen will his intellect agree to the meeting. In Tolstoy’s interpretation of John’s Gospel, Nicodemus says to Jesus:

You do not bid us keep the Sabbath, do not bid us observe cleanliness, do not bid us make offerings, nor fast; you would destroy the temple. You say of God, He is a spirit, and you say of the kingdom of God, that it is within us. Then, what kind of kingdom of God is this?

Jesus answers:

Understand that, if man is conceived from heaven, then in him there must be that which is of heaven.

Nicodemus, not understanding, next says:

How can a man, if he is conceived of the flesh of his father, and has grown old again enter the womb of his mother and be conceived anew?

Jesus now takes the discussion to a deeper level:

Understand what I say. I say that man, besides the flesh, is also conceived of the spirit, and therefore every man is conceived of flesh and spirit, and therefore may the kingdom of heaven be in him. From flesh comes flesh. From flesh spirit cannot be born; spirit can come only from spirit. The spirit is that which lives in you, and lives in freedom and reason; it is that of which you know neither the beginning nor the end, and which every man feels in him. And, therefore, why do you wonder that I told you we must be conceived from heaven?34

Still Nicodemus doesn’t get it, at least not at first. Nor do we. But Jesus knows that he will and that we will. The seed has been planted. He has done what he could where the obstinacy of the intellect still rules. Now life will have to be the teacher, confirming through experience what couldn’t be accepted on faith.

The lesson of life is that the seed, having fallen into the ground and in order to release its potential, must die. From life’s crises and traumas, from the small and large deaths the ego suffers, the life of the spirit is born. Having endured the traumas of childhood and adolescence, having passed through the crises of independence and identity, having suffered the pain of the ego’s crucifixions and the shadow self’s humiliations, in all these ways a person’s perception of the “real” and the “not-real” makes an about-face. The “real I” and the “not-real I” trade places: what is “flesh” and what is “spirit”; what is “mind” and what is “soul”; what is “temporal” and what is “eternal.” Having been differentiated, these opposing forces are now ready for reconciliation--the divided to be reunited. The total, the whole Self has learned that to be human is to be on both sides of the equation: the physical self who perceives Reality sequentially—as in time--and the spiritual Self who experiences the Whole simultaneously—as in eternity.

From the greater perspective of the Eternal Now the gap between the seen and the unseen closes. The “here” and the “hereafter” are no longer two places. “This side” that is called life and “that side” that is called death interpenetrate. From the perspective of spirit, the greater Reality is seen as a multidimensional, interconnected whole. Totality, Suares insists and physicists are beginning to agree, “is an indeterminate number of universes . . . with no dividing walls.”35

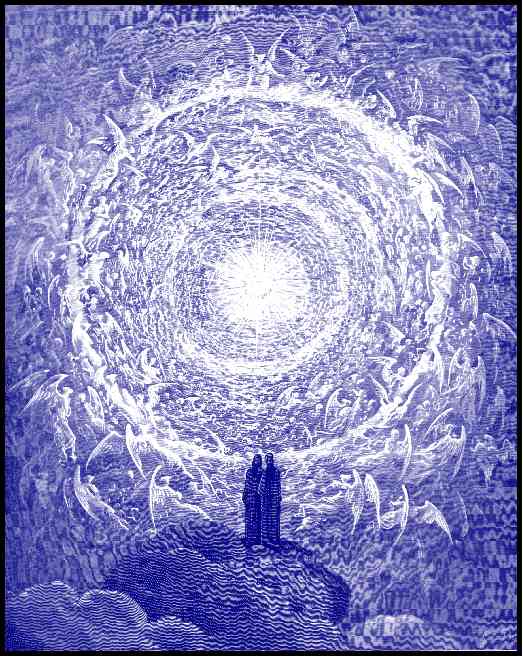

Looking back from journey’s end, incarnation will be seen to have been a

passage through time in order to gain the perspective of eternity.

Separation from the Whole will be seen to have been in order to return as a

consciously knowing inseparable part of the greater Reality. In the

end the returning soul will take its place in Dante’s Celestial Rose, which

is not just an image, but an actual attracting force at the Center by which

the soul is being drawn home. (Plate 9)

Plate 9

Dore’s Interpretation of Dante’s Vision of the Celestial Rose

__________________________________

Chapter Three Credits

Figures

1 - The Essential Outlines of Light Waves, a Dove in Flight, and Tongues

of Fire

2 - The Star of the Transcendent Self

Plates

1 - The Nativity, by Giotto, 1267-1337, The Arena Chapel, Assisi

(contact: Scala)

2 - Good Shepherd, Reredos in Chapel of the Good Shepherd, Washington

National Cathedral

3 - The Call of Peter and Andrew, by Duccio, 1255-1318, National

Gallery of Art, Washington, D C

4 - The Holy Family, Early 19th Century Polish folk art,

from Folk Art of Europe, 1990, Rizzoli International Publications,

Inc, 300 Park Ave So NY, NY 10010

5 - The Presentation, by Giotto (see III-1 above)

6 - Flight to Egypt, Giotto, (see Plate 1, above)

7 - Christ Disputation with the Doctors, by Duccio, c 1255-1315,

The Maesta, Museo dell’Opera del Duomo, Siena (contact: Scala)

8 - The Baptism of Christ, Stained Glass Window, St Matthew’s

Episcopal Church, San Andreas CA, design by Wm Rundstram (1999), McKeever

Studios, 830 A Sonoma Blvd, Vallejo CA 94590, (707) 648-0630, photo by

Richard Duval.

9 - The Empyrean, by Dore, 1832-1883, from The Dore Illustrations

for Dante’s Divine Comedy, Dover Publications, inc. 180 Varick Street,

NY, NY, 10014

Chapter Three Notes

1 Jung, op cit, Psychology and Religion,

CW 11, para 267

2 Isaiah 9:6

3 Jung, op cit Aion CW Volume 9 Part II, para 146

4 Ibid, para 128

5 Ibid

6 Rabbi Joel Dobin, The Astrological Secrets of the Ancient Hebrew

Sages, Inner Traditions, NY, 1977, p 33

7 Ibid, para 147

8 Matthew 3:16

9 Acts 2:2-3

10 Edinger, op cit, Christian Archetype, p 28, with Philo quote

from Esther Harding’s Woman’s Mysteries, Ancient and Modern. pp.124

11 Luella Sibbald, The One With the Water Jar, Guild for

Psychological Studies, San Francisco, 1978, pp 5-6

12 Phillips Brooks’ “O Little Town of Bethlehem”

13 Colossians 1:27

14 Ignatius of Antioch, “Epistle to the Ephesians,” The Ante-Nicene

Fathers, vol. 1, p 57, quoted in Edinger’s Christian Archetype,

p 36

15 From Psalm 96

16 Edinger, op cit, Christian Archetype, p 36

17 Heinrich Zimmer, in Spiritual Disciplines, Papers from the

Eranos Yearbooks, edited by Joseph Campbell, Bollingen Series XXX 4,

Princeton University Press, NJ, 1960 p26

18 Frederick Buechner, Wishful Thinking, A Theological ABC,

Harper & Row, NY, 1973, p 65

19 Luke 3:32-35

20 Luke 2:37-38

21 Kahlil Gibran, The Prophet, Knopf edition, NY, 1963, p 17

22 Revelations 12:1-6

23 Hosea 11:1

24 Luke 2:40

25 Luke 2:46

26 Mark 6:3

27 Matthew 13:55

28 Matthew 3:15-17.

29 Psalm 63:1

30 Edward F Edinger, The Bible and the Psyche, Inner City

Books, 1986, Toronto, pp 5

31 Matthew 4:8

32 Luke 8:26-36

33 Fritz Kunke, Creation Continues, Word Books, Waco, 1973, p

284

34 Luke 4:18

35 John 3:1-8

36 Suares, op cit, p 2

Go To Chapter IV

Return to Higher Ground Home

Return to Murraycreek Homepage